Inside China’s State-Owned Enterprises (SEOs) and their assistance to Chinese espionage

Written by: Sarah Geesaman

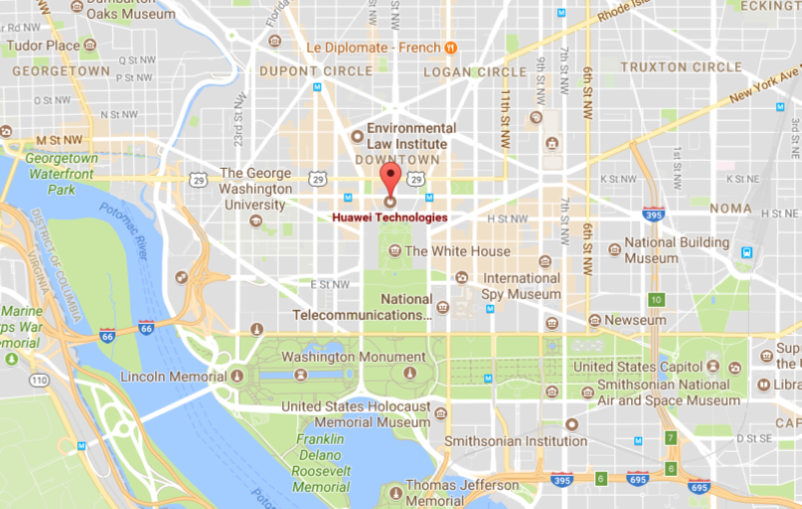

China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are a veritable gold-mine of economic espionage potential; one that has likely been a substantial asset to China in the past and will only continue to grow in importance as the Communist Party tightens its grip on SOE internal operations. In 2012, the U.S. House of Representatives’ Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) released an investigative report detailing concerns that Huawei and ZTE, two of China’s most prominent international telecommunication companies, were spying for the Chinese government.1 Among others, the report cited the companies’ failure to clarify their U.S.-based operations and the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) role in their leadership structure as key reasons to distrust Huawei and ZTE’s intentions. Yet despite overtly increasing party control over major Chinese industries in recent years, the public has largely ignored the espionage threat posed by Chinese SOEs since 2012. As Xi Jinping’s plan to reassert party control over SOEs begins to take effect, the U.S. would do well to consider the threat that CCP control of Chinese economic assets poses to her intellectual property and national security.

China has a long history of successful economic espionage targeting technology to facilitate its military, economic, and political expansion. China’s economic espionage is primarily accomplished through the cultivation of a wide array of human sources who collect and relay small pieces of intelligence, which the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and 2PLA then piece together.2,12 This methodology, though slow, has been effective for China. Among the most popular targets of Chinese economic espionage are US military organizations and supporting technology developers and producers; solar energy developers; nuclear power plants; and metal producers.4,5 In a span of twenty years, Chinese intelligence successfully pieced together U.S. nuclear technology. In 2004, China paid a Chinese-American couple $500,000 for computer parts which allowed them to construct their own versions of the U.S. Tomahawk cruise missiles. In 2016, a Chinese national employed in the U.S. was caught selling sensitive military program documents which he had stolen from United Technologies.3 Although these individuals were eventually apprehended, the wide pool of potential spies from whom China’s espionage network gathers information makes detecting or preventing economic espionage incredibly difficult. Among the assets recruited by the MSS are Chinese tech workers and students temporarily residing in overseas, ethnically Chinese Americans, and anyone capable of contributing to their cause.2

Economic espionage is often collected by individuals or companies around the globe to help China gain military and production advantages, as well as exploit foreign system vulnerabilities. As illustrated by China’s success in capturing nuclear and Tomahawk technology, economic intelligence may be collected by individual human sources. However, it may also be collected by Chinese companies themselves. This was one of HPSCI’s primary concerns in the cases of Huawei and ZTE.1 As telecommunication companies, they had access to a broad base of private and public systems and data. Funneling such data back to MSS and 2PLA could provide China with insight into political, military, and economic decision making across the country. The most common effects of economic espionage are associated with the actual theft of developed technology: namely, the leveling of military advantages through theft of recently developed technology and the undercutting of economic development by obtaining plans for the final product without incurring research costs.12 Less commonly discussed are the effects of economic espionage on the creation and exploitation of supply chain and infrastructure weaknesses. If a nation-state gains insight into the mechanisms undergirding a foreign powers’ critical infrastructure, they may be able to locate and exploit previously unknown weaknesses in that infrastructure. If they supply that infrastructure, they can build weaknesses themselves and exploit them at a later date. This was the crux of the HPSCI’s worries regarding Huawei and ZTE’s penetration of the U.S. telecommunication networks.14 The CCP’s control over SOEs and influence on many private-owned enterprises (POEs) raises concern on its own, but that concern grows exponentially when one considers the power the CCP has to demand compliance with MSS and 2PLA intelligence needs.13

Economic espionage is often collected by individuals or companies around the globe to help China gain military and production advantages, as well as exploit foreign system vulnerabilities. As illustrated by China’s success in capturing nuclear and Tomahawk technology, economic intelligence may be collected by individual human sources. However, it may also be collected by Chinese companies themselves. This was one of HPSCI’s primary concerns in the cases of Huawei and ZTE.1 As telecommunication companies, they had access to a broad base of private and public systems and data. Funneling such data back to MSS and 2PLA could provide China with insight into political, military, and economic decision making across the country. The most common effects of economic espionage are associated with the actual theft of developed technology: namely, the leveling of military advantages through theft of recently developed technology and the undercutting of economic development by obtaining plans for the final product without incurring research costs.12 Less commonly discussed are the effects of economic espionage on the creation and exploitation of supply chain and infrastructure weaknesses. If a nation-state gains insight into the mechanisms undergirding a foreign powers’ critical infrastructure, they may be able to locate and exploit previously unknown weaknesses in that infrastructure. If they supply that infrastructure, they can build weaknesses themselves and exploit them at a later date. This was the crux of the HPSCI’s worries regarding Huawei and ZTE’s penetration of the U.S. telecommunication networks.14 The CCP’s control over SOEs and influence on many private-owned enterprises (POEs) raises concern on its own, but that concern grows exponentially when one considers the power the CCP has to demand compliance with MSS and 2PLA intelligence needs.13

Xi Jinping’s efforts to increase control over SOEs and private-owned enterprises (POEs) create an explicit connection between the CCP and Chinese industry which is far more than symbolic. With some 70% of Chinese private industry in compliance, China’s requirement that private businesses maintain a party committee is nothing new.6 In the case of SOEs, party committees technically sit above corporate boards.7,8 Recent developments, however, indicate the CCP’s intentions to reassert control over Chinese economic assets–not only those officially identified as SOEs, but also POEs. First, the controlling documents of many SOEs have been rewritten to explicitly affirm the central role of the CCP in their governance, indicating that the CCP has no intention of decreasing involvement in SOEs, despite devastating effects on China’s economy.8 Second, SOEs like Tianjin Realty Development, which voted against the creation of a party committee to review all “major company issues” prior to their submission to the board, was brought into compliance in a span of just 5 months.10 Third, European joint investors in partnerships with SOEs are now facing political pressure from China to change the terms of their ventures to allow the CCP the final say on investment decisions.6 Fourth, party committees are running “anti-corruption” campaigns and have put a number of Chinese businessmen and women in prison.11 Even though CCP leadership often undermines the financial viability of an industry, most of China’s banks are also SOEs and they prioritize loans for companies in line with the CCP.9,13 The message this sends to POEs is clear: compliance with CCP goals and requests is financially advantageous, and refusal to do so will be disastrous.

The precise nature of China’s economic espionage may be unclear, but the implications for U.S. national security are not. The HPSCI was right to assert that the U.S. should continue to view Chinese penetration of telecommunications networks with suspicion and develop new legislation to better address the threats posed to such systems. However, the U.S. would be remiss if it considered the telecommunication industry the only one posing a substantial risk to U.S. intellectual property, infrastructure, and national security. In a world where the CCP holds as much sway over SOEs and POEs, every company is a potential accessory to espionage. ■

-

-

House of Representatives Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, “Investigatie Report on the U.S. National Security Issues Posed by Chinese Telecommunications Companies Huawei and ZTE,” 8 October, 2012, https://intelligence.house.gov/sites/intelligence.house.gov/files/documents/huawei-zte%20investigative%20report%20(final).pdf

-

Peter Brookes, “Legion of Amateurs: How China Spies,” Heritage Foundation, 31 May, 2005, http://www.heritage.org/commentary/legion-amateurs-how-china-spies

-

The United States Department of Justice, “Chinese National Admits to Stealing Sensitive Military Program Documents From United Technologies,” 19 December, 2016, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/chinese-national-admits-stealing-sensitive-military-program-documents-united-technologies

-

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, “Chapter 2, Section 3 – China’s Intelligence Services and Espionage Threats to the United States in 2016 Annual Report to Congress,” 16 November, 2016, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Annual_Report/Chapters/Chapter%202%2C%20Section%203%20-%20China%27s%20Intelligence%20Services%20and%20Espionage%20Threats%20to%20the%20United%20States.pdf

-

The United States Department of Justice, “U.S. Charges Five Chinese Military Hackers for Cyber Espionage Against U.S. Corporations and a Labor Organization for Commercial Advantage,” 19 May, 2014, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-charges-five-chinese-military-hackers-cyber-espionage-against-us-corporations-and-labor

-

Michael Martina, “Exclusive: In China, the Party’s push for influence inside foreign firms stirs fears,” Reuters, 24 August, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-congress-companies/exclusive-in-china-the-partys-push-for-influence-inside-foreign-firms-stirs-fears-idUSKCN1B40JU

-

Jennifer Hughes, “China’s Communist party writes itself into company law,” Financial Times, 14 August, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/a4b28218-80db-11e7-94e2-c5b903247afd?mhq5j=e6

-

“Reform of China’s ailing state-owned firms is emboldening them,” The Economist, 22 July, 2017, https://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21725293-outperformed-private-firms-they-are-no-longer-shrinking-share-overall

-

Christopher Balding, “China Takes on State-Owned Firms,” Bloomberg, 10 August, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2017-08-10/china-takes-on-state-owned-firms

-

Tom Mitchell, “China’s Communist party seeks company control before reform,” Financial Times, 14 August, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/31407684-8101-11e7-a4ce-15b2513cb3ff?mhq5j=e6

-

Wendy Wu, “How the Communist Party controls China’s state-owned industrial titans,” South China Morning Post, 17 June, 2017, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/economy/article/2098755/how-communist-party-controls-chinas-state-owned-industrial-titans

-

Peter Mattis, “The Analytic Challenge of Understanding Chinese Intelligence Services,” Studies in Intelligence 56.3, September 2012, https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol.-56-no.-3/pdfs/Mattis-Understanding%20Chinese%20Intel.pdf

-

13 Curtis J. Milhaupt and Wentong Zheng, “Beyond Ownership: State Capitalism and the Chinese Firm,” Columbia Law School, 2014, http://www.law.columbia.edu/node/5344/beyond-ownership-state-capitalism-and-chinese-firm-curtis-j-milhaupt-and-wentong-zheng

-

Bill Gertz, “Chinese telecom firm tied to spy ministry,” The Washington Times, 11 October, 2011, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2011/oct/11/chinese-telecom-firm-tied-to-spy-ministry/

-